Overview

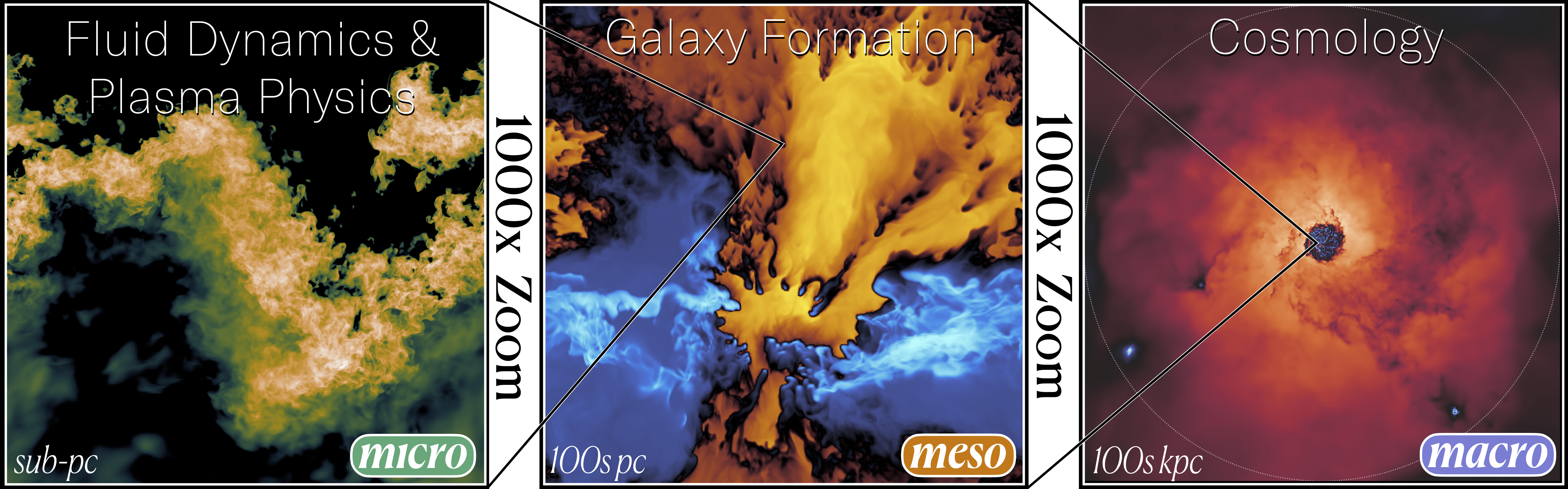

My research focuses on uncovering the fundamental physics that drive a wide range of astrophysical and physical phenomena. I develop intuitive and robust theoretical models, guided by cutting-edge simulations, to explore the intersections of fluid dynamics, plasma physics, galaxy formation, and cosmology. My work also bridges disciplines, drawing connections to areas like climate modeling and pure mathematics. This interdisciplinary approach has advanced our understanding of diverse systems, including ocean turbulence, combustion, protoplanetary disks, cosmic rays, magnetic reconnection, galactic regulation, and cosmological inference. By addressing questions that probe the core principles of our universe, I aim to reveal the underlying physics shaping these complex systems.

Much of my research naturally focuses on galaxies because they sit at the crossroads of modern astrophysical inquiry. As the luminous beacons that trace the structure of the universe, galaxies are essential for testing cosmological theories. They also serve as the environments where stars and planets are born, and where dramatic events like black hole mergers unfold. Yet, despite their significance, we still lack a complete understanding of the forces that shape their evolution. Galaxies live in a delicate balance: the gas within them should, in theory, rapidly collapse under gravity to form stars or be driven out by the intense energy of stellar explosions and black hole activity. Why, then, do galaxies persist for billions of years without exhausting their gas supply or tearing themselves apart? The answer lies in a complex interplay of inflows and outflows of gas, regulated by processes occurring on scales as small as individual stars and as vast as the regions between galaxies. My work seeks to uncover the physical principles behind these galactic gas flows and the mechanisms that govern the life cycles of galaxies.

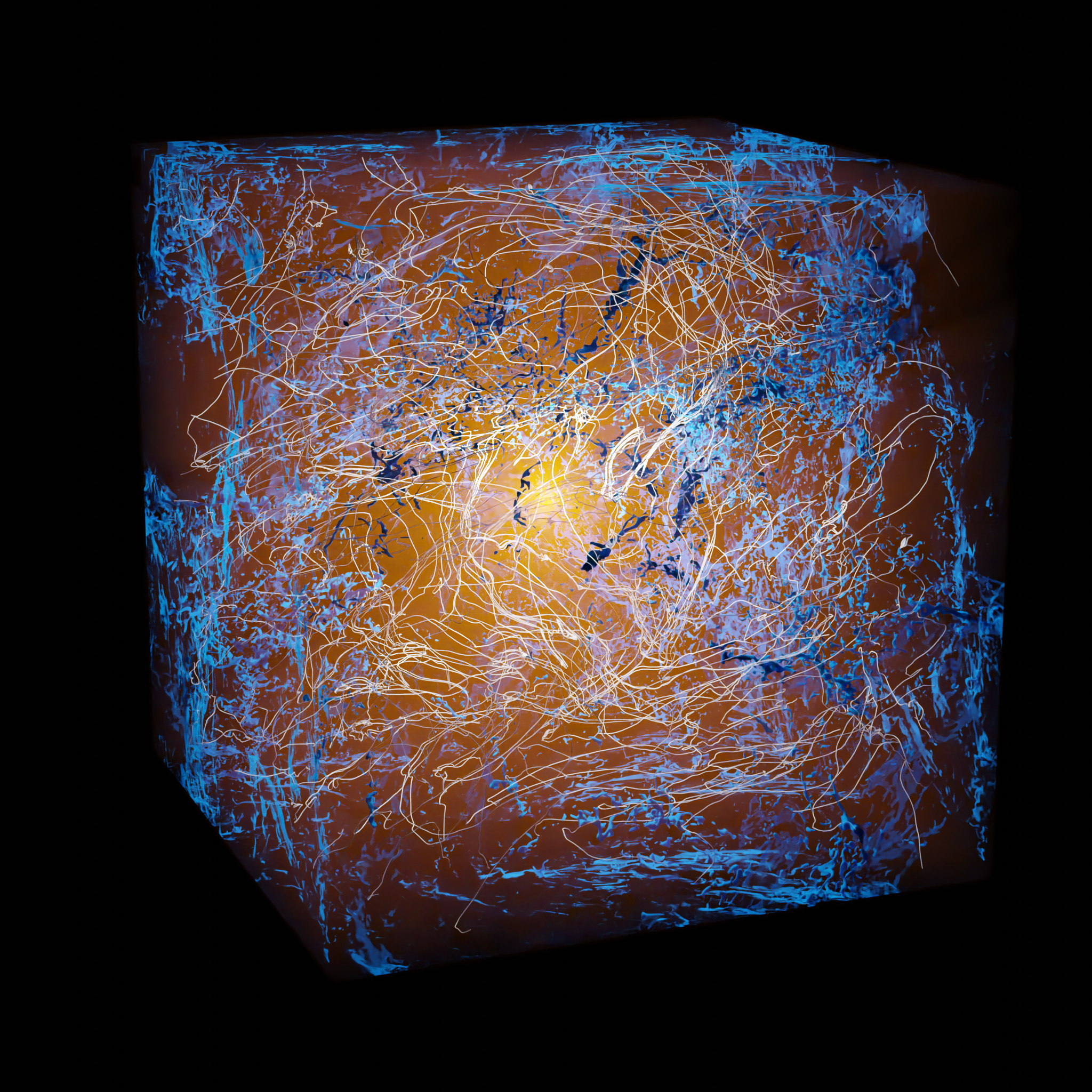

To tackle these questions, I use a blend of analytical theory and advanced simulations to connect the smallest scales—where turbulence, magnetic fields, and cosmic rays dictate gas behavior—with the largest, where galaxies interact with their cosmic surroundings. This multi-scale perspective not only reveals how galaxies sustain star formation and regulate black hole growth but also contributes to broader efforts to understand the universe’s evolution. By developing new tools and collaborating across disciplines, I strive to illuminate the hidden physics that shapes galaxies and other astrophysical systems.

Recently much of my work has focused on running exascale simulations of the magnetized turbulent interstellar medium (ISM) and circumgalactic medium (CGM) to understand the physics of cosmic ray scattering. You can see a recent press release about this work here, and an article about it here.

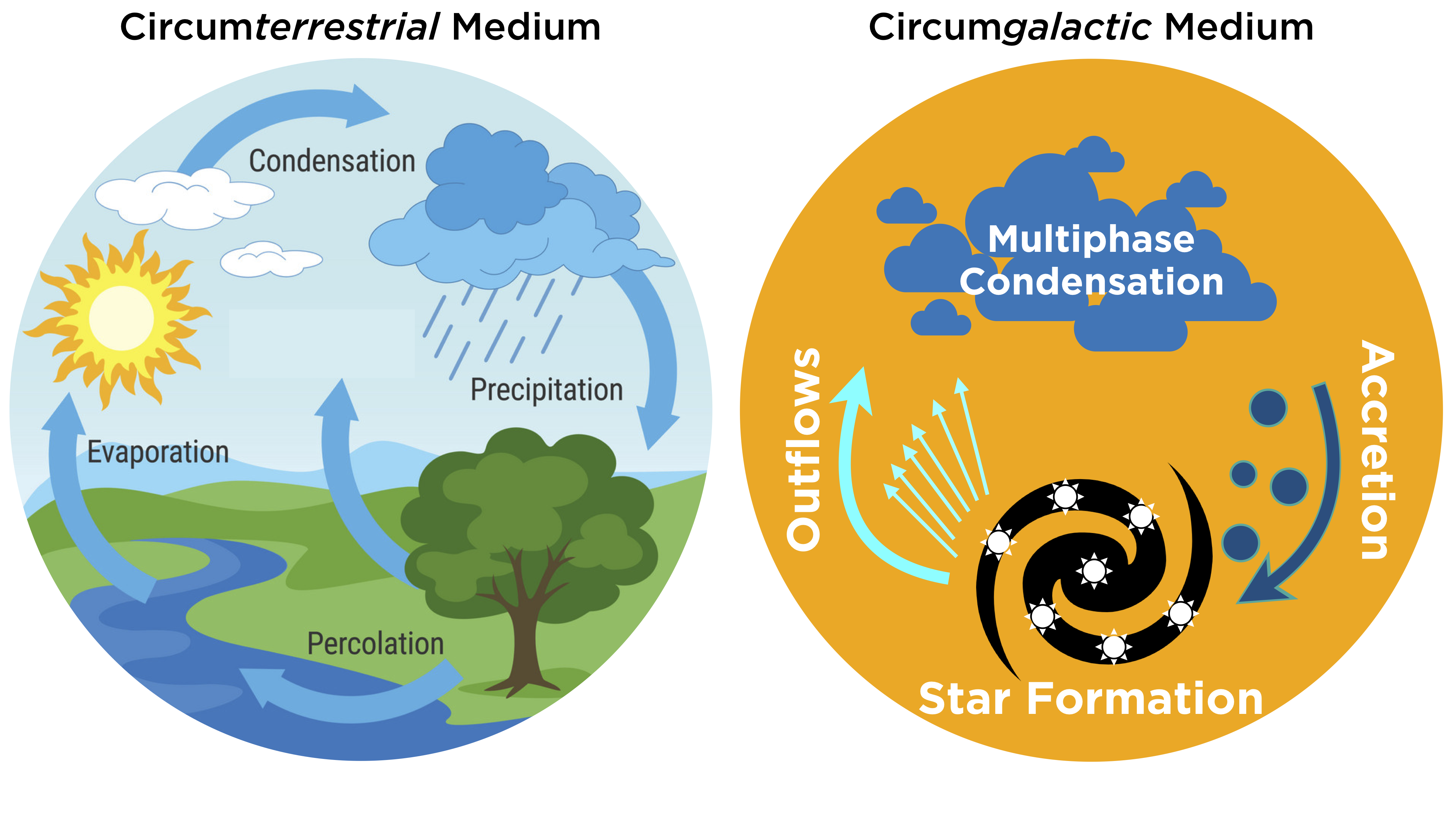

I like to use the water cycle here on earth as an analogy for how I look at galaxy formation. In the water cycle water is heated and evaporates, then condenses in the form of clouds, and then it precipitates back down to earth where it nourishes and fuels living creatures before being evaporated all over again. In galaxies we can replace water with gas (mostly hydrogen and helium) and see that it is quite similar. Gas in the CGM condenses into clouds, which under certain conditions precipitates down to the galaxy. When this gas reaches the galaxy it is pure star fuel! Out of the freshly precipitated star fuel new young stars form. These stars release lots of energy and some of them explode as supernovae, which can launch gas back out of the galaxy and up into CGM. In this way what I work on—galactic gas cycle—can be seen as the galactic version of terrestrial hydrology!

An interesting part of the galactic gas cycle is the way that it self-regulates similar to a thermostat in a heating system. The more the CGM can cool and form clouds, the more gas makes its way to the galaxy, and the more stars form. As more stars form, more of them explode as SNe, which combine together to drive a wind out into the CGM. This wind will heat the CGM and prevent new clouds from forming, which limits the supply of star fuel and thereby weakens the wind until clouds can form and the process stars over again!

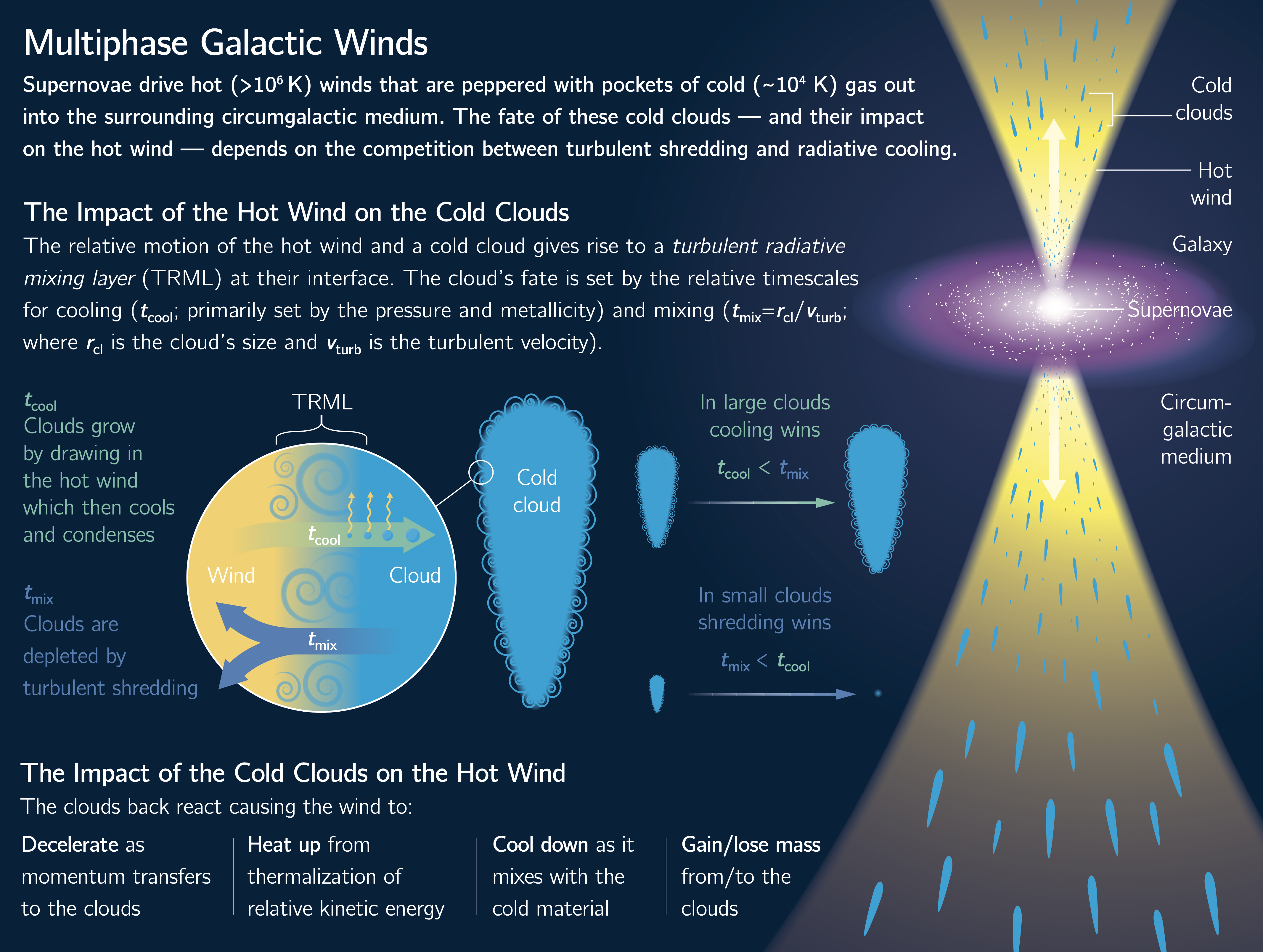

Multiphase Galactic Winds

Circumgalactic Medium

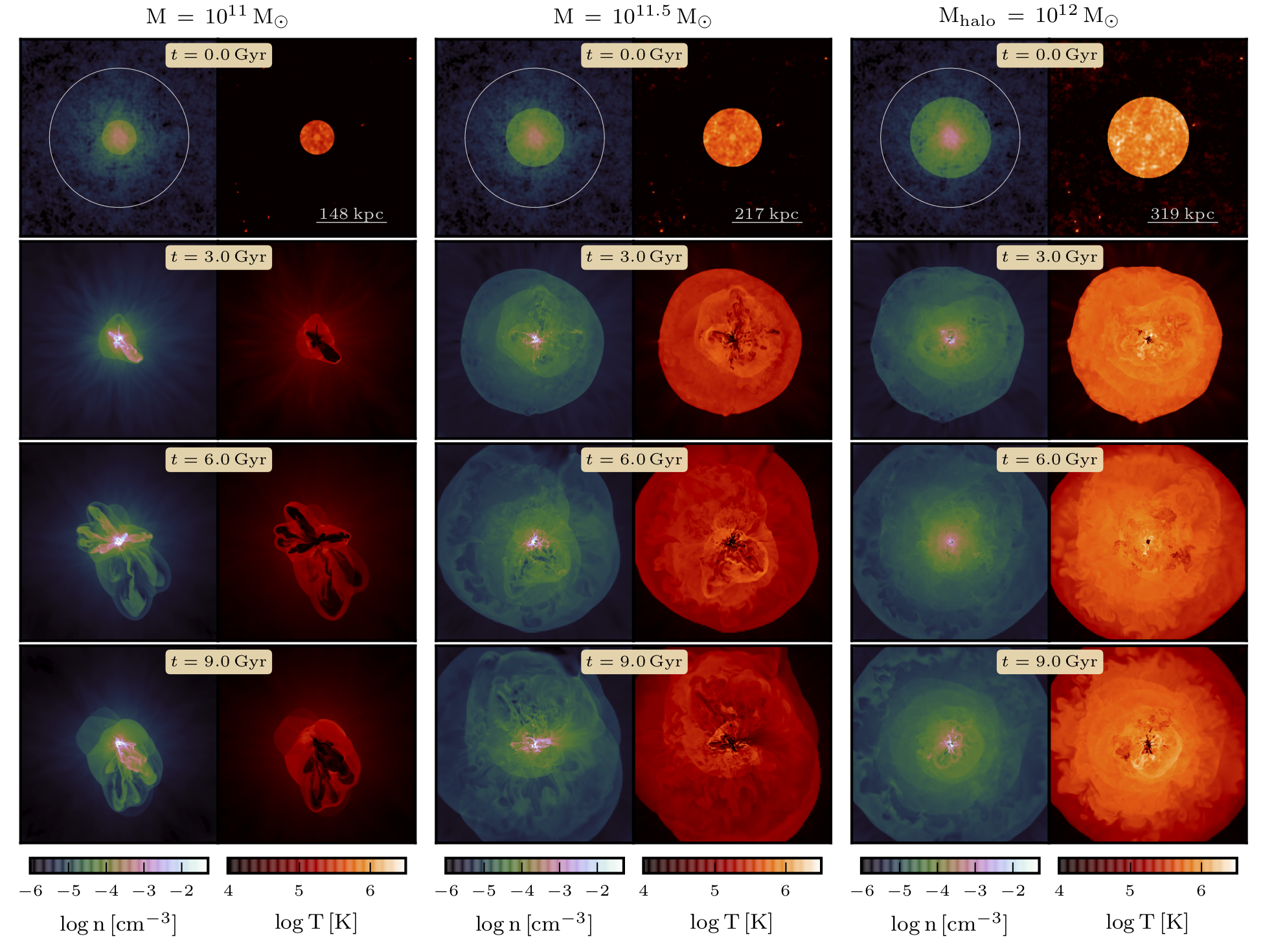

Galaxies grow by accreting new gas. This gas must come from the massive reservoir of material that surrounds all galaxies–the CGM. The CGM is where many competing forces meet. Gas from outside a galaxies dark matter halo feeds the CGM from without either smoothly, in filaments, or in the form of smaller galaxies. Gas from inside the galaxy is violently ejected into the CGM in the form of winds. These flows interact with the gas already present in the CGM that would otherwise cool and fuel the galaxy and can lead to the CGM being a dynamic, turbulent environemnt.

Although the CGM plays such an important role in galaxy formation it is exceedingly hard to study. Observationally, it is nearly impossible to detect the CGM because of its low densities and high temperatures. Ground breaking recent work has begun to map out the CGM of other galaxies one pencil beam at a time using absorption by cold CGM gas in the spectra of distant bright objects like galaxies and quasars. In the (near?) future new telescopes may enable the CGM to be directly measured in emission, which would teach us much more. Theoretically, the CGM is also hard to study because of the incredible range of scales involved. On the largest scales the CGM of a single galaxy roughly the size of the Milky Way can extend to Mega-parsec scales. However, the dynamics of the whole system can be set by the processes by which cold and hot gas mix and cool, which takes place on the scale of parsecs or less. This means that there at least six orders of magnitude in scale at play in the CGM!

In line with the nature of the CGM my work on the CGM has focused on many scales. On the largest I study how the bulk properties of the CGM are determined by winds, and cosmological accretion, and how this regulates galaxy growth. On intermediate scales I study individual patches on the CGM and how turbulence, magnetic fields, and cooling set the temperature distribution and ionization state. On the smallest scales I study how individual cold clumps mix as they move through the hot ambient medium.

Galactic Winds and Feedback

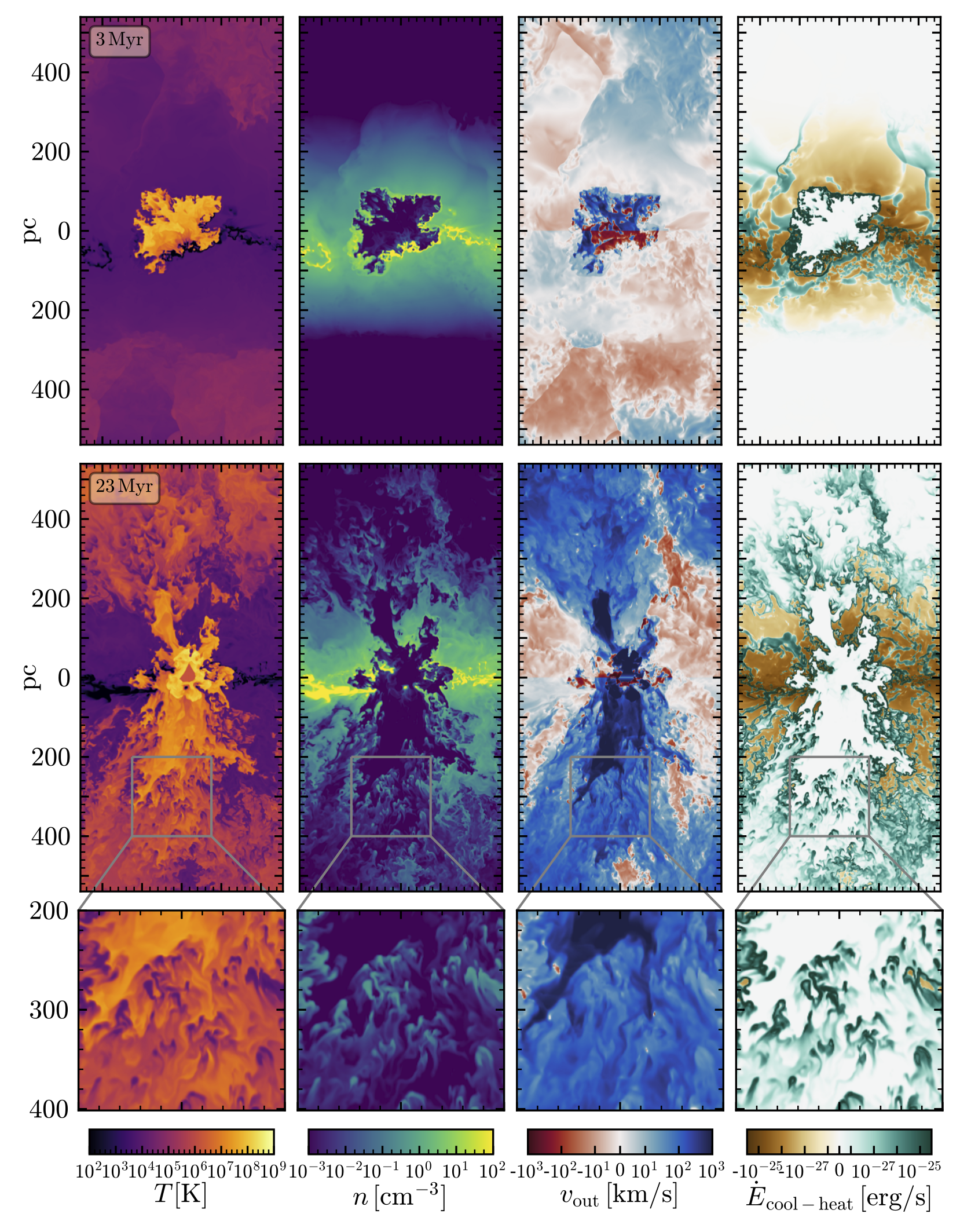

When a star explodes as a supernova (SN) within the interstellar medium (ISM) of a galaxy it releases prodigious amounts of energy into its surroundings. On the scale of a whole galaxy the energy released by the collective explosions of many SNe is responsible for energizing the ISM and for driving galactic winds. The stirring and ejecting of ISM gas by SNe is believed to play the dominant role in determining the relative inefficiency with which galaxies up to the mass of our own Milky Way turn gas into stars. It is therefore essential for any theory of galaxy formation to explain how energy is deposited into the ISM in the form of heat and turbulent motions (and cosmic rays), and to explain how mass and energy are sent flying out of the galaxy.

In order to isolate these crucial processes my collaborators (Eliot Quataert, Claude-Andre Faucher-Giguere, and Davide Martizzi) and I have simulated the collective effect of numerous SNe going off in patches of the ISM and in entire galaxies. We have found that by taking into account the natural clustering of SNe due to the clustered nature of star formation the efficiency of SN feedback is greatly enhanced. The winds that result from clustered SNe can be very strong, carrying nearly as much mass out as is turned into stars and carrying nearly all of the energy ejected out into the surrounding circumgalactic medium. The implications of the large energy flux into the inner CGM has not been fully explored yet but points to a picture in which galactic winds primarily impact galaxy evolution by preventing future accretion, as opposed to ejecting gas out of the galaxy that has already accreted (although both are certianly at play).

Plasmoid Mediated Magnetic Reconnection in the ISM

Protoplanetary Disks

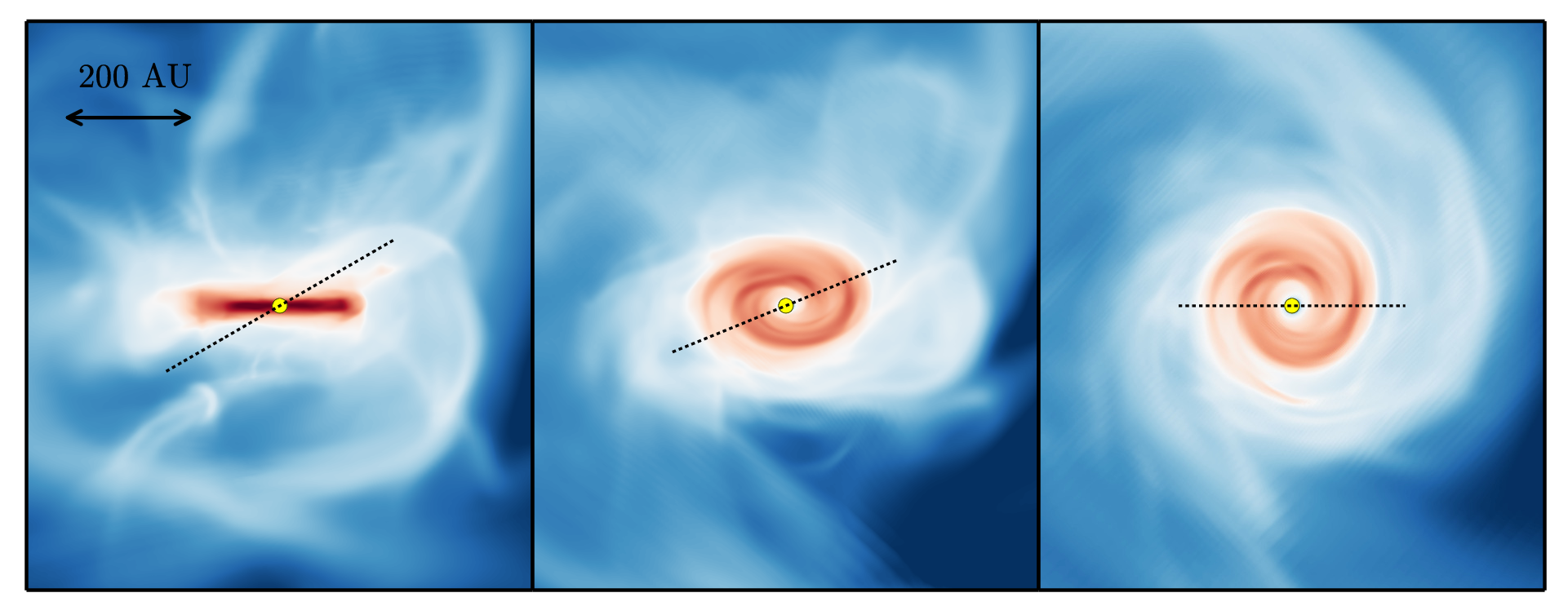

The Kepler mission found many Jupiter mass planets with very short orbital periods (P<10 days). How these “hot Jupiters” migrated to such close-in orbits is debated. Observations of non-zero stellar obliquity—the angle between the host star’s spin axis and the hot Jupiter’s orbital axis—seemed to favor orbital angular momentum loss due to tidal dissipation from the star-planet interaction during close periastron passages induced by torques from a distant third body (Fabrycky and Tremain 2007). However, using hydrodynamic and magnetohydrodynamic simulations of protostar formation, I demonstrated that a wide range of stellar obliquities may be produced as a byproduct of forming a star within a turbulent environment. I developed a simple semi-analytic model that reveals this connection between the turbulent motions and the orientation of a star and its disk. Our results are consistent with the observed obliquity distribution of hot Jupiters implying that the misaligned hot Jupiters may have instead migration due to tidal dissipation in the disk (Goldreich and Tremaine 1980). We have also applied this same concept to explain the observed misalignment of protostellar binaries outflows (Offner et al. 2016).